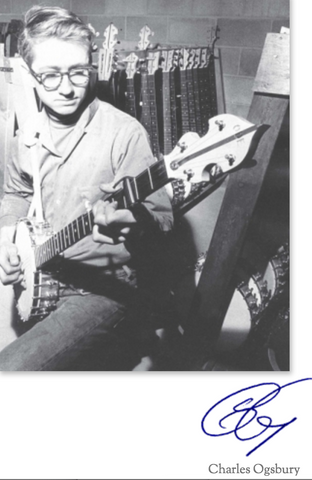

Interview with Chuck Ogsbury of Ome Banjos

We had the chance to sit down with Chuck Ogsbury, the founder of Ode banjos and Ome banjos recently. We discussed the history of the Ome banjo company, some of his banjo building beliefs, how he goes about designing new instruments, and more. Chuck Ogsbury is a living treasure in the banjo community and has been building great banjos since the late 1950s.

When did you first start making instruments?

I was going to college here in Boulder (Colorado) for engineering and got interested in my last year there in folk music. I grew up in Kentucky so I grew up with a lot of bluegrass and old time music back there.

What part of Kentucky?

Louisville. I actually started playing guitar when I was 16 back there, but I didn’t have a good teacher and had a lousy instrument, so I didn’t go very far.

When I got into college, it was the late ‘50s - I was actually walking through the area between the Engineering building and the student union and heard this incredible music in this little area where the mountain climbers hung out in, and it turned out to be some guy playing the banjo and Judy Collins playing the guitar - she was going to school there then. It kind of blew me away, so I started getting involved with people who played folk music back then. It was you know, the late ‘50s, the Weavers at Carnegie Hall album blew me away like a lot of people in my generation.

So I started getting back into playing guitar and then ended up getting into the banjo. I found some old timers around here who played instruments. And then I started picking up these old banjos, guitars, and mandolins in the junk shops in the Denver/Boulder area here, and fixing them up and selling them to my student buddies and giving them a couple lessons.

Anyway… instruments were not easy to find here in the West compared to the East Coast. There was a lot more older music culture going on, and a lot of banjo shops around like the Boston/Philadelphia area and what not.

How did you know how to fix up these instruments?

I just kind of taught myself. My mother was in the antique business and I grew up around a lot of fine wood and metal working. I got into trading antique firearms when I was 12 years old. By the time I was a teenager I was a pretty significant dealer in antique firearms there. I’d fix up a lot of old Civil War and late 19th century weapons. To me they’re kind of like art forms in wood and metal actually. Of course a lot of banjo guys also like antique firearms. They’re really similar, they just do totally different things. I kind of call it a common denominator - an art form in wood and metal. So I had some experience working with wood and metal and just applied that to musical instruments. I didn’t really know what I was doing too much.

And then - instruments were hard to find and I was still in school, and I just had this flash one day of making banjos with an aluminum pot. So I had a friend who was a machinist in the physics department at CU (University of Colorado Boulder) and we had a prototype sand cast pot made up, and I stuck what I think was a Kay banjo neck on it, and when we put it together it sounded really good, so I just decided - “Wow, this sounds so good” and … at the time it was really hard to find old, you know, vintage instruments, and at the time the long neck 5-string was coming into vogue. I actually bought one - a used Vega longneck. I looked at it all over and I thought it was lacking - actually the fret spacing was not correct. It had some of the frets closer to the head were slightly larger spacing than the one above it, this sort of thing - it just wasn’t made that well. I thought “Wow, I can make a better instrument than this for less money!” So anyway, I decided to make 100 of these things.

That’s a lot of em!

Yeah… I don’t know why I did that! Anyway, I had kind of an antique gun collection, I sold all of that and it financed my banjo project.

I met an old woodworker, a Swedish woodworker - he must of been pushing 80. He taught me a lot about woodworking. We made the necks in his shop. That was the first 100 banjos. They were all long necks and they sold for 70 bucks.

What kind of pot was it?

Sand cast aluminum. Just 11”, sand cast aluminum. It was pretty simple. Totally simple. So it was pretty inexpensive to make and especially for the price, they sounded really well.

How did you get the pot cast? You went to a foundry?

There was a foundry up the road that sand cast aluminum and bronze. So, you make a pattern out of wood and they would make the castings. And actually, we didn’t even turn them down on a machine. They were polished on a belt polisher. We didn’t even have to finish them. They had the silver look. They looked like an old banjo you know. And they sounded decent and the price was right.

And then I actually made a run of cases - hardshell cases out of plywood and solid wood sides. 25 bucks a piece I was getting for those. I probably lost money on each one of those.

What was the brand name on these?

Ode. Ode banjos.

So that was the beginning of the Ode banjo company?

Yup. To tell you the truth, I don’t ever remember thinking “Oh, this is gonna be a business.” I just didn’t think that way. It was just something I wanted to do, and then as fast I could put those darn things together, people would come by and buy - all word of mouth. So I thought “Wow, there must be something to this.” So the next batch I ran some standard length necks - 5 strings. And then I moved into 4 string banjos and then 6 string banjos.

Were these resonator banjos?

I can’t remember the exact progression. I know that right after the long necks I did a standard length 5 string.

So basically, you just taught yourself? You weren’t an apprentice to somebody?

Well, at this point it was all self learning as far as the banjo part goes. The 70 or 80 year old Swedish woodworker taught me a lot about the woodworking part and my physicists and machinists in the physics department helped me with the metal parts. So I got that going and just kind of winged it for the next 2 or 3 years. There were a number of people around here (in Boulder), there was a guy named Al Campton who played banjo since the ‘20s. I learned a lot about instruments from him. There were some other young players that I learned a lot from about playing and how to make banjos work for the players. I was also playing myself.

It went on, we started the Ode banjos. We probably made about 1500 banjos, all with aluminum pots. I also kept experimenting. I did a lot of designs on the pots. Different shapes, weights, and this sort of thing. Always putting things together and having local musicians playing what I did.

The turning point came in about 1964. This young kid hitchhiked out from Athens, Ohio and he had a dulcimer he made. He had hitchhiked out to see about working in our shop. He had heard about us. I did hire him. We struck up a really strong friendship and creative relationship. Turns out, he knew more than me about old instruments - not making, but the whole vintage world His name is Kix Stewart. He stayed there for a year and in a year we totally reworked my product line. We went in to making the wood rim banjos which ended up being the Baldwin style A, C, D, F, whatever.

So we made the whole wood rim line of banjos. We even started making my own planetary tuning pegs. I was the first one of the modern makers who started making those geared planetary tuning pegs. Before Schaller, Stew Mac, or anybody else.

My company had every oddball in it. We were kind of like bohemian beatniks. There was like 10 people working there. Everybody had their own key and they would come and go as they please. Everybody was crazy. In the meantime, my buddy Kix decided to go back to Athens, Ohio.

The stress was getting to me. Having to always pay the rent, pay the wages, and dealing with all of these crazy people. I got burned out and decided to sell the business. So I sold it to Baldwin Piano and Organ.

How old were you when you sold the company?

I think I was 26.

So you were really young still.

Yeah. I worked for Baldwin for 6 months helping them get set up, but I just wanted to kind of be a free spirit and ended up wandering around for a while, living in different places, but came back to the mountains in Boulder.

What year was this that you sold the company?

1966. I happened to be at Newport Folk Festival in 1965. The folk thing had died out.

When Dylan went electric…

We had camped out there, and they had a rehearsal that night before the whole thing started. There was about 25 of us there. I was sitting next to Harry Tuft who runs the Denver Folklore Center. Pete Seeger had just done his act. Then Bob Dylan came on, backed up by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Harry and I just looked at each other, we didn’t say a word, but what went through our minds was “Oh shit. Our whole profession is trashed!” Our jaws just dropped!

When did you get interested in building banjos again?

In about 5 years. I got interested with a guy working with me on construction. He was a drummer and said, “I hear you made banjos, wanna do that again?”.

That was like 1970 when acoustic music was coming back again. I never thought I’d build another banjo again. But I was living up in the mountains and I had this shop and I started building banjos again and called it Ome.

How much square footage was that shop?

About 2500 square feet. I did kind of the same mistake again because I’m a free spirited person. One redneck and a bunch of hippies. I had horses up there just running wild.

Did you ever run into issues building instruments at such a high elevation?

Banjos aren’t like guitars. They’re plywood. They’re laminated. The necks might move a bit but Colorado is a great environment to build in. No - occasionally I’ll get one of those instruments that were made up there but they’re perfect. Colorado’s been a good place to build.

We were up there for 2 years. I loved it. My partners wanted to make it more of a business so we moved the company Ome down to Boulder. We’re still in Boulder. My partners have all left and I ended up with the entire company. I never planned it that way.

I went to a psychic this one time and for some reason she picked up that I built instruments and she said “Oh, you’ve done it for several lifetimes”. For some reason I got the music curse.

Tanya tells me you have a pretty extensive shop.

We are probably in the top 10 in the world for new banjos.

I like old stuff, and I’ve had a lot of old banjos, but most of them - they’re falling apart a lot of the time. The animal glue is coming apart and what not. New instruments are a lot easier to deal with for sure.

I also believe we are in a golden age for instrument building - when you look at what the builders such as yourself, Deering, Collings, Bourgeois, etc. are putting out there.

Yeah. This is definitely a golden age for fretted instruments for sure. A lot of great builders are out there.

How many people currently work at Ome?

There’s just Tanya, myself, and 2 other people working here.

How many banjos do you make a year now?

We were up to about 175.

How long have your people been with you?

My two guys have been here for about 20 years or so.

Are you the sole person who comes up with the design elements of new banjos?

Pretty much, yup. I’m pretty much the sole person. There are some other artists that do some of the engraving and one off art work, but I do about 90 plus percent of the design work.

How did you learn to do some of that design?

Well, I did a little drawing. But actually, my mother was a painter, and so it kind of runs in the family. Over a lifetime I’ve found out that I like to design and build things. I’ve done a fair amount of design and building in the construction industry. I’ve designed my own buildings. I love to design new things. No formal training.

What we’re doing now, is some of the nicest things we’ve done. Now, more than ever.

Do you use CNC?

Yes. We sub out our CNC work. CNC is better as it makes it perfect. We still do a huge amount of hand work.

How would you describe some of the different tone woods that you offer on a banjo? I know you offer maple, mahogany, walnut, and cherry. Are there any others?

I love wood. I’ve always loved wood. I’ve worked with wood since I was a kid. I love it all. I like good solid hardwoods. To me they all sound good. Actually at Ode I used to make Brazilian rosewood banjos. The pots were still maple but the necks and resonator veneers were Brazilian rosewood. When that dried up, we went to Indian rosewood. We made a fair amount of rosewood Omes. I really don’t like wood that’s too bright, and that really heavy wood. We pretty much stopped doing that. I actually like the sound of the softer woods, the mahoganys and some of the softer maples, and walnut. To me, everything that we make now sounds good. You know, any species of wood can vary quite a bit. When people think, “maple sounds this way and walnut sounds that way, mahogany sounds this way”, there’s some truth to that, but it can vary a large amount. We can make pots that are walnut, still mostly it’s maple, but we can make walnut pots, cherry pots, mahogany pots. We make some of everything. To me it all sounds good. But… it’s hard to do all this stuff you know. It kind of drives you crazy. So, then again, it’s a matter of balancing. You gotta stay in business so you gotta keep your costs down. Every time you do all this different stuff, it runs the cost up. But I’m kind of addicted to doing different things. I like to see all the different banjos coming out made with different woods and that sort of thing.

You offer a varnish finish on some banjos and a lacquer on others. Do you spray poly on any of your banjos?

We’re using a catalyzed lacquer. It’s kind of like a lacquer. It’s not real thick. I don’t like a real thick finish. But again, a banjo is different than a guitar. When you have a guitar, you don’t want to lay on poly on a guitar. You do a thin lacquer finish on an acoustic guitar. A banjo is closer to an electric guitar where you could put a thick finish on there and it wouldn’t effect the tone.

So you don’t think there’s a tonal difference between varnish and lacquer?

I don’t think on a banjo there is a tonal difference between varnish and lacquer. I think there’s so many bigger things to deal with like the head being at the right tension and your tailpiece. There are so many really relatively simple things to deal with, your setup is huge.

Being an old gun nut, I like oil finishes. And, I’m an environmentalist, so I like using natural, non toxic finishes. I like to feel the wood. I’ve always liked that, but it was traditional to use lacquer, so we used lacquer for years and years. When I started making Ome in 1970, I think it’s when I started using the oil finishes on our low end line. I’d see these things come back 10 or 20 years later and they still looked great. You just rub a little oil on it.

Most of what we’re doing now is oil. Even on some more expensive bluegrass banjos. There’s nothing like lacquer to bring out the beauty of curly maple. It gives it that optical effect. But, then if you scratch it, you got a major job to finish it and buff it up. Oil is a lot easier. Right now we’re doing mostly oil varnish - tung oil.

Not linseed oil?

There’s some various combinations of the oil we use. But, pretty organic stuff. Several coats. It still takes a lot of work, but generally we can do it less expensively than lacquers. We’re doing a lot of that. But, it’s all good. You know, when somebody wants a really flashy banjo with the curly maple jumping out at you, we put lacquer on it.

Oil also tends to be faster than lacquer. It plays faster. Martin uses a satin finish on all of their guitar necks because it’s faster. When you polish it up, the finish gets stickier.

Yeah. Especially here in New Orleans where it is very humid.

What is your hardware generally made of? Is it brass?

Generally most of our metal is machinable brass. The tone rings have a special formula when you get to the bluegrass bronze tone ring.

How do you keep the aged brass or bronze hardware that you offer from turning green?

We’ve been doing a lot of this aged brass for about - I think it’s going on 6 years. I don’t think I’ve had any complaints of it turning green. It’s pretty amazing stuff. I’ve seen a few of the older ones and they haven’t turned green. Actually some of our oxidation has worn off a little bit. You could re-oxidize it, but it seems to be working really well. Again, I’m an old gun nut and I love the old guns that were made with brass and wood and seldom have I seen them turn green. They just get this light patina on them. It looks really nice. Especially with wood. That’s why we went with the wood armrest too. I added that wood armrest. It goes really well. It makes the pot look better and you don’t get allergic reactions to it.

I’ve even made some polished brass banjos. When it’s new, you can’t tell it from gold.

I’ve seen a lot of our nickel banjos come back, corroded to the point where it has pits all in it. The nickel can get trashed out. I believe the brass probably holds up better than the nickel.

What’s your take on the tonal difference between dowel sticks vs. coordinator rods and the adjustability factor?

When we set them up, we try to set those things up so that you don’t really need to adjust them. I know the pot can warp, and the two rim rods (coordinator rods) seem to give a more solid structure because the pot can move over years, and there’s nothing as solid as the two rim rods. On our other models, it’s still held on with the two lag bolts which I believe, because you can really tighten those with two attachment spots, with either a lug nut or a rim rod. I can set up any banjo either way. Basically it’s the same banjo. You have the two lag bolts, and you can either use two metal rods or on our old time banjos we use a wooden rod instead of a metal rod.

And then put a nut on the other as you don’t need two wooden rods in there. But it seems to be working really well. If you need to adjust it, like we have some washers in there, you could take a washer out if you want to increase the angle and crank it down more. But again, so far we haven’t had a problem. Also, if you did need to reshape the neck, you don’t have to steam the glued dowel stick. You just take the lag bolts out and reshape the back of the neck. It’s a lot easier. So far, it seems to be working really well.

We’re doing it a little bit different now. I’m making the dowel sticks a little longer so it’s a tighter fit on our next generation of stuff coming through here.

Do you have any new models coming out and how do you come up with a new model?

I usually come up with an idea, then make a prototype. We have so much stuff, the guys hate it, and we can’t keep up with it all.

The last one that came out, I really like this last one, the Oracle.

It’s kind of like cars, you start out with a Toyota Rav that’s a real tiny little thing and 10 years later its the size of an SUV. I’d look at it and think to myself, it’d look a little better with this or that. I might spend 2 years designing every inlay pattern. It’s easy for me to keep evolving it for 2 or 3 years, until I get it right and I say that’s good enough - I’m not doing anything more.

Do you still play music?

A little bit. I like music. We live in a little quaint mountain town that has world class music.

Do you ever perform?

I’m a closet musician. I identify with Bill Collings (of Collings Guitars and Mandolins) (pictured below).

To me, Bill Collings, as far as a builder goes - he’s probably my number one hero. He’s a guy who does incredible things. I kind of always wanted to get to his level of production but never could. But anyway, my theory is most builders are frustrated musicians. They are probably guys who wanted to play. But building and designing instruments is different than playing them. It’s a different function of the brain. So I’ve found out that you know, I love music, and I have a good ear for it and a good feel for it, but I just am more of a design/builder than I am a musician. I like to go to bed early and get up early. Musicians have to stay up til 3 and 4 in the morning. Sleep til noon. I could never do that.

Who are some of your favorite musicians?

I like a lot of music of the ‘70s. I also like traditional music from all over the world. I’m not a banjo fanatic. I love African music. Irish music. Greek music. Just all of it. Some of the Asian stuff gets too weird for me, but I like indigenous music.

If you weren’t a banjo maker, what do you think you’d be doing?

I would have loved to have been an artist. More design, more painting. I’m very visual.

What do you like to do in your spare time? What are some of your hobbies?

I’m an outdoor adventurer. Mountain climb, ski, bike, travel around the world.

I got to meet and visit with Mr. Ogsbury at the ODE factory in Boulder in the early sixties, and later his daughter Tanya at IBMA. Just by listening to him talk and reading this article it’s quite evident the Chuck Ogsbury is a musical genius when it comes to making banjos. I have the upmost respect for him. I still have my 1963 aluminum body ODE. It reminds me of the sound of my 1924 Vega tuba-phone open back with an ODE longneck.

Leave a comment